by Angelo F. Elmi and Heather J. Hoffman

Introduction

The prospect of learning how to write functioning code while also learning statistical concepts in a class can be a daunting challenge for students, especially those without adequate quantitative training. In this blog, we describe two teaching approaches for programming with statistical software, one that is most common (“error-free”) and one that is less common (“error-full”). The goal was to identify ways to increase students’ confidence by helping them persist when encountering the inevitable error messages that occur when running erroneous code. We describe our experiences based on teaching programming with SAS software®, but the principles described apply to other programming languages.

Error-free vs. Error-full Teaching

Students must learn how to write functioning code to obtain the results of a statistical analysis. A traditional approach to teaching this focuses on writing correct code from the start. We refer to this as “error-free” teaching, in the sense that a student’s learning experience may be free of errors if they never make them. While some students may be able to successfully learn how to write a program this way, many students will make errors that need to be debugged. Without experiencing how to resolve an error message, these students may become discouraged and lose motivation to continue. We aimed to contrast this style of teaching with a more “guided” one that intentionally exposes students to erroneous code. We refer to this approach as “error-full”, in the sense that students are purposefully exposed to code containing instructor-created errors to develop their debugging skills. In this approach, students are taught the basic principles of correct code as in the error-free case, but the lesson is followed by guided exposure to common errors with an explanation from the instructor on how to diagnose and correct the errors.

Coding errors can arise in many ways, but we classified them into two general types. First, there are errors that are directly reported by the computer program, such as in the log window or by red text in the enhanced editor window. Such errors are often called syntax errors. The debugging sessions here focused on interpreting the error message in the log to diagnose and fix the code. A second kind of programming error can occur when the user has written a program that is syntactically correct but does not produce the desired result. Such errors are often called semantic errors. This situation can be more difficult for students to diagnose because there is no direct indication, such as a red error message, indicating the existence of a problem. Here, the debugging session requires showing students how to spot-check the dataset to identify problems.

Next, we will describe these methods with some specific examples using SAS software®. Further details on these teaching methods and examples are available in an article published by Hoffman and Elmi (2021) in the Journal of Statistics and Data Science Education.

Example 1 (syntax error): Subsetting IF and WHERE Statements

Our first example is a situation in which students are asked to create data subsets with SAS software®. There are two ways to do this in SAS®: use an IF statement or use a WHERE statement. These statements can be used interchangeably in many situations, but some subtle differences in how they work can cause errors if students use them without fully understanding the differences.

Behind the scenes, a program data vector in SAS is a storage place in memory where a data set is built, one row at a time. Data are read into the program data vector either from an existing data file or from a raw file source, such as a text file, and code from the DATA step provides instructions on how to build the data in each row of the dataset. For more details on building data sets with SAS, see Delwiche and Slaughter (2019).

One area of coding in SAS where the program data vector plays a subtle but important role is writing code to create subsets of a SAS data set based on some logical conditions. The differences between subsetting WHERE and subsetting IF statements can sometimes be mixed up leading to a syntax error. In short, a subsetting WHERE statement executes before the data are read into the program data vector. Therefore, if used improperly, SAS software would be attempting to subset data that do not yet exist, and a red error message would be produced in the log window. On the other hand, a subsetting IF statement executes after data are read into the program data vector, so it will not suffer from this inconsistency. A student who incorrectly believes these statements are always interchangeable may try to use the WHERE statement in place of the IF statement inappropriately.

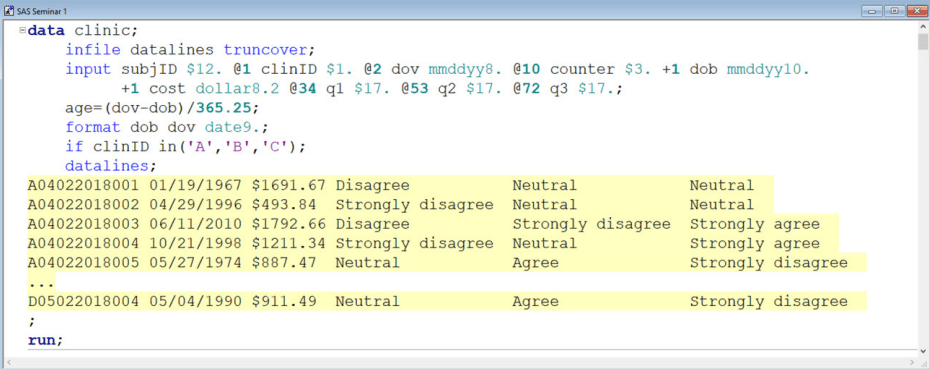

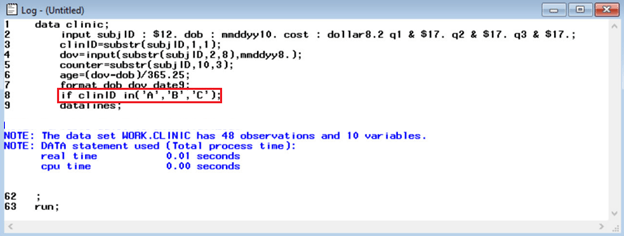

In the error-free lecture, we showed students the code below, which demonstrates a correct way to use a subsetting IF statement. The resulting log window is shown as well.

If a student were to incorrectly try to subset using the WHERE statement shown below, the program would not execute.

Instead, an error message would appear in the log window as shown below.

While the error message is routinely solvable for an experienced programmer, a student who is learning for the first time may not be able to fully understand what is being communicated in the log window.

In the error-full teaching approach, we showed students this error as part of the guided session to ensure that they were exposed to this kind of error message before attempting to perform a task like this on their own. We explained clearly that the phrase “No input data sets” referred to the fact that the incorrect WHERE statement was leading SAS software to try to subset data that did not yet exist. Hence, it was necessary to use the IF statement as shown in the error-free code.

Example 2 (semantic error): Order of Operations

In the first example, the error message in the log window informed the student of an error’s existence and prevented them from proceeding until they corrected the error. Another kind of error can occur when syntactically correct code performs an erroneous calculation (i.e., semantic error). The student can be misled here into thinking their code is correct without realizing that there is an error until trying to run a statistical analysis on the incorrectly created dataset.

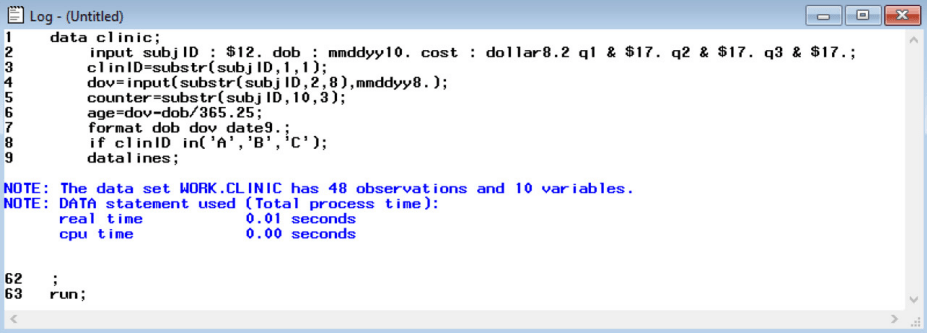

In the error-free lecture, again, the correct code was presented as shown above in example 1. However, now we consider a case where students who do not follow the order of operations may omit the parentheses when creating the age variable as shown below.

The resulting log window provided below does not show any signs of an error in the code, which may lead to the incorrect belief that the dataset is correct.

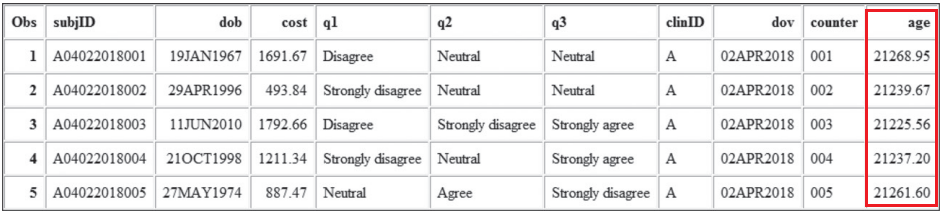

In the error-full session, the instructor would emphasize the need to do spot checks of the data to reduce the chances of this kind of error. For example, in this case, an instructor might simply suggest checking the values of the dataset to see that they make sense. As shown below, this simple check would easily reveal this kind of error as the values stored for age do not make sense.

In other situations, the instructor might emphasize performing some routine calculations as a spot check. For example, in another application, it is possible that the date of visit might be stored as a date earlier than the date of birth, suggesting a possible data entry error. In this case, the instructor might suggest checking the data for negative age values either by running a PROC step to find the minimum age (which would be a nonsensical negative number) or by conditionally subsetting to find all the rows with negative age values.

Conclusion

The error-free and error-full teaching methods are described in more detail in an article published by Hoffman and Elmi (2021). There, we describe a series of seminars that motivated this contrast of teaching approaches and present some additional examples of error-free and error-full teaching. The overarching goals were to help students understand how to recognize incorrect code and develop independent programming skills. As we have shown above, and we show further in the article, errors can occur in a variety of ways; some are obvious, while others are more subtle. By intentionally showing students how these specific errors can occur, we hope that they will spend less time spinning their wheels when working independently and be more confident in writing functioning code. Some preliminary data based on surveys given after the seminars indicated most students prefer the error-full teaching method. We believe that debugging should be a standard component of all programming courses, and the error-full method of teaching provides a useful potential framework for how it can be implemented.

Contributing author Dr. Angelo Elmi is an Associate Professor in the Department of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics at The George Washington University School of Public Health. He is the program director of the Biostatistics Concentration for the MS Program in Health Data Science. He has extensive teaching experience in courses at the Master’s and Doctoral level such as Linear and Generalized Linear Models, Longitudinal Data Analysis, Categorical Data Analysis, as well as more general courses in Biostatistics and SAS programming. Dr. Elmi’s research interests include application of statistical methods to Maternal and Child Health, Health Policy, Sports Medicine, and Pediatric respiratory infection risks. His methodological interests include Longitudinal Data Analysis and Joint Modeling of Longitudinal and Survival Data.

Contributing author Dr. Heather Hoffman is a Professor and Vice Chair of the Department of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics. Dr. Hoffman is the MPH Biostatistics Program Director, and she serves as Chair of the school-wide and departmental Curriculum Committees. She teaches advanced quantitative and programming courses on campus and online, including Biostatistical Applications for Public Health, Use of SAS for Data Management and Analysis, Applied Survival Analysis for Public Health Research, Advanced SAS, and Quantitative Methods. She has received Excellence in Teaching awards and is a member of the Master Teachers Academy in the Milken Institute School of Public Health. Dr. Hoffman’s diverse research portfolio focuses primarily on HIV/AIDS, breast cancer and education innovation research. She has co-authored more than 60 articles in the peer-reviewed literature and contributed to more than 90 presentations at scientific conferences. She serves as the biostatistician on multiple grants and contracts funded through the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation. Dr. Hoffman serves as the faculty advisor for multiple masters and doctoral students each year. Dr. Hoffman is a member of the American Statistical Association and is the publicity officer and portal reviewer for the Teaching of Statistics in the Health Sciences Section. Dr. Hoffman also serves on the United States Transuranium and Uranium Registries Scientific Advisory Committee.

References

Delwiche, L. and Slaughter, S. (2019). The Little SAS Book (6th edition).

Hoffman, H. J., & Elmi, A. F. (2021). Do Students Learn More from Erroneous Code? Exploring Student Performance and Satisfaction in an Error-Free Versus an Error-full SAS® Programming Environment. Journal of Statistics and Data Science Education, 29(3), 228-240.

Leave a comment